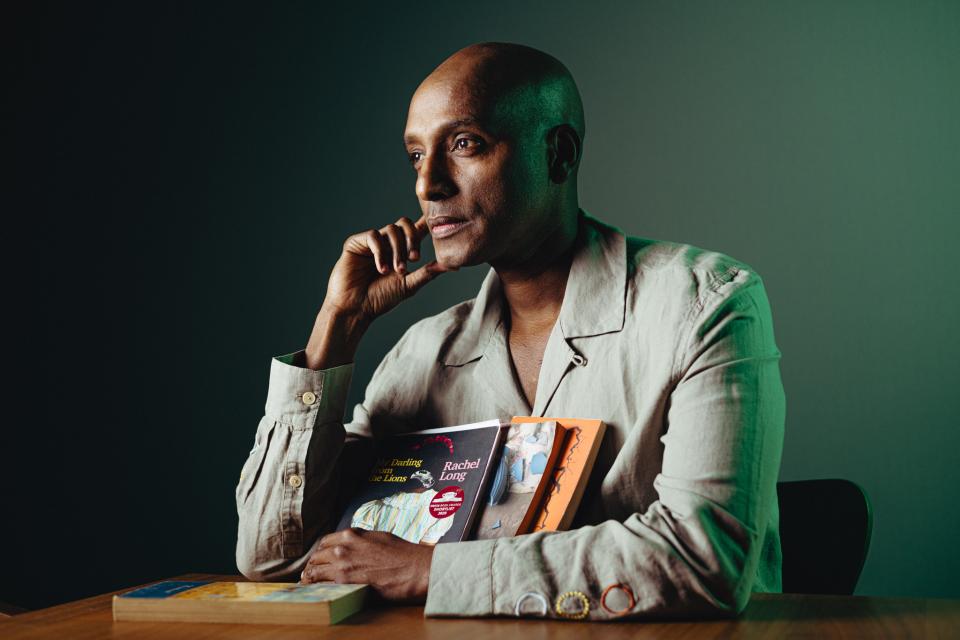

Sulaiman Addonia’s World of Reading

Schopenhauer famously said that reading is thinking with someone else’s head. But what is it that we hope to find in the other person’s head? Peace and quiet, distraction, knowledge? Welcome to the World of Reading, a series of interviews in which we talk about the role of reading, beauty, and language. In this instalment: the writer Sulaiman Addonia.

Interview by Matthias M.R. Declercq

Translated by Sandy Logan

-> naar de Nederlandstalige versie van dit artikel

“Reading is the perfect conduit into an unknown world,” says Sulaiman. “Curiosity as the mainspring of literature. It was in Jeddah (a Saudi Arabian city on the Red Sea) that I first read Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist. I identified with Oliver as I also grew up without parents. Through Dickens, I also got to know more about British society, a world that was unfamiliar to me.”

Sulaiman Adonnia - now a renowned international author -ended up in Jeddah as a teenager after an odyssey on the fringe of society. His story begins in Om Hajer, a tiny Eritrean village. In 1975, amid the Eritrean war of independence, government troops herded the villagers into a field on the pretext that an important official was visiting. They then started spraying the crowd with bullets. Addonia, who was just a baby, and his family somehow miraculously survived the massacre. Months later, his father was beaten to death by strangers, prompting his mother to flee to a refugee camp with Sulaiman, his brother, sister and grandparents. Addonia still has a scar on his nose from where he fell off a camel, a scar that forever reminds him of his flight to Sudan. Over the next eight years, he moved from camp to camp before he and his brother Salah migrated to Saudi Arabia, where his mother worked as a live-in servant in a palace, where she was at the whim of her employer. Sulaiman Addonia is one of the keynote speakers at the upcoming Culture & Mental Health: Refugees, an international conference that is jointly organised by Iedereen Leest. He is our conduit into a world that is unknown to many.

Salih

Addonia: “Books were liberating for me, a migrant in Saudi Arabia, where they tell you that everything is either black or white. It was my brother who provided them to me. Having lost his hearing, he turned to books, which he obtained through a well-connected Sudanese intellectual whom he befriended. All books that were banned by the regime. Just like Western cinema, which was also banned or censored in Saudi Arabia. We were only shown images that had been given the green light by the regime. So you can see how reading a rebellious book like Oliver Twist would be a thrilling experience for a 13-year-old. And Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih (a Sudanese author who wrote about the heavy toll of colonialism on Sudan). I cannot not mention this book. I return to it time and again. You can sense how Salih writes straight from the heart, guided by his imagination, his characters, and not by existing narratives or narrative structures. He didn’t care about censorship.

That is why it came as such a shock later in life, when I ended up in London with my brother, to find that even in the UK, only part of reality is reflected in literature. Of the thousands of new titles published in the UK in 2016, fewer than 100 were by British authors of a non-white background. This is not right, so in that sense, this is also censorship.”

Sulaiman Addonia organised the Asmara Addis Literary Festival In Exile as a counterpoint to this censorship. In Brussels, the city where he finally ended up after falling in love with a Belgian in London. “I want to provide a platform for as many voices as possible,” he says. “Voices from many different countries and the most diverse backgrounds. This is our only way of grasping people and society, the only way to challenge reality.”

Addonia uses the word challenging often. It also typifies his own work. After the success of The Consequences of Love (2008, a love story about a 20-year-old Eritrean refugee in Saudi Arabia) and Silence is my Mother Tongue (2018, about life in a refugee camp), he recently published The Seers (2024, about a homeless Eritrean migrant in London), a 155-page book that consists of a single paragraph. Addonia wrote it on his iPhone during lockdown while walking around the ponds of Ixelles.

“I don’t expect literature to be healing,” he says. “On the contrary. Above all, literature should be challenging and thought-provoking, like The Story of O by Pauline Réage (the pseudonym of Anne Desclos) and A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing (by Eimear McBride).”

The Story of O is a cult book, a sadomasochistic novel that was published in 1954. Some 40 years after its publication, it was finally revealed that its author was Anne Desclos, a translator and editor at Gallimard Publishers. A girl is a half-formed thing seeks controversy elsewhere, in the tale of a young woman and how she relates to her brother, whose brain was damaged by the removal of a tumour. “It’s absolutely one of my favourites,” says Sulaiman. “It unfolds in the narrator’s mind, with all the accompanying feelings, emotions, sexuality, everything. It all seems irrational, but irrationality ignites the imagination. Instead of proffering well-finished, clean, escapist stories, it should confuse us, raise questions, seek out the boundaries.”

Lorca

“When I was studying Economics of Development at University College London, I read a lot of non-fiction. I became almost obsessed with the IMF (International Monetary Fund). I wanted to understand why the African economy had so much potential and why so many countries remained poor, which is why I devoured academic articles. Non-fiction is still very much a part of my World of Reading. I read newspapers and magazines; I want to know what is going on in the world. But I also read a lot of poetry – Federico García Lorca, Fernando Pessoa, Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, Emily Dickinson, E.E. Cummings, Jay Bernard, Rachel Long - preferably poets who abandoned existing techniques and embraced the avant-garde. I also attach great importance to oral histories. There were no books in the refugee camp in Sudan, but my mother and maternal grandmother told me long stories in their own special way. I owe my highly descriptive style entirely to them. And to cinema. Even before I could read, I used to watch films, which really helps me now because it allows me to develop scenes in an almost cinematic way. Obviously, each medium has its own voice, its own style, and this has taught me that there is much more to read than books, more to watch than films. Reading also means stepping out into the street, looking at people, reading people, reading trees, looking the world in the eye.”

“I also attach great importance to oral histories. There were no books in the refugee camp in Sudan, but my mother and maternal grandmother told me long stories in their own special way. I owe my highly descriptive style entirely to them.”

Culture & Mental Health: Refugees. International Conference. 28 and 29 November 2024, Museum Dr. Guislain, Ghent.

Asmara Addis Festival (in Exile): 29 and 30 November 2024, Den Teirling, Ixelles.

Worlds of reading

Discover more inspirational interviews with readers.